Hundreds of years ago, two young men in what is now Mexico were beheaded and buried at the foot of a Mayan pyramid. Their remains – and those of other young men who may have been sacrificial victims – were recently discovered by archaeologists excavating the Moral-Reforma archaeological site in the Mexican state of Tabasco.

The 13 skeletons were discovered just 40 feet (more than 12 meters) from “Structure 18” — a pyramid-shaped monument south of the site’s main temple — according to a statement from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). Archaeologists found the skeletons buried about a foot (0.3 meters) deep and are beginning to determine who they belong to and what happened to them.

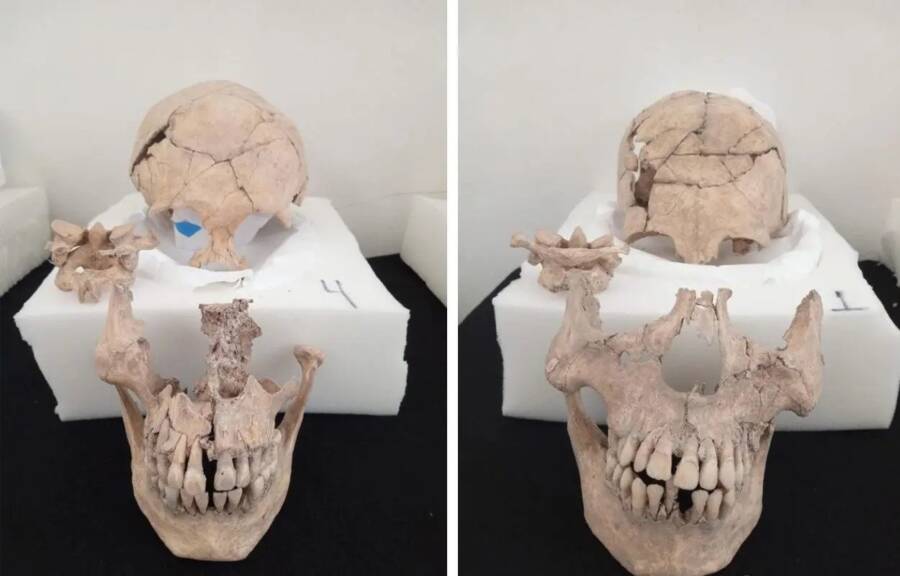

Archaeologists have found 13 mysterious skulls, at least two of which are definitely victims of ritual sacrifice. Photo: Allthatsinteresting

The Maya were known to sacrifice prisoners of war, but it’s not known whether these newly discovered skulls actually belonged to prisoners of war, Live Science reports. But we do know for sure that they were all between the ages of 17 and 35 and were likely buried between 600 and 900 B.C.

And two of the skulls bore clear signs of violence.

Perhaps the most common of the strange skulls ever discovered are elongated skulls. Current science suggests that these deformed skull shapes are due to an old custom of the Aborigines, who squeezed the heads of newborn babies so tightly that they became deformed. Photo: Allthatsinteresting

As INAH explains, “transverse cuts were observed on the bone shaft related to the craniocervical junction.” Miriam Angélica Camacho Martínez, a physical anthropologist from the INAH Center, further explains that these marks on the bones seem to suggest “the use of a sharp object to remove the skull, and we know this because the neck and the mandible maintain their anatomical relationship, however it is difficult to determine whether this injury was the cause of death or was performed after the death of these individuals.”

The archaeologists also determined that five of the skulls had unusually elongated shapes, which appeared to have been intentionally elongated during childhood. This purposeful deformation was practiced by the Maya, as well as other ancient civilizations in Asia, Europe, and the Americas, Live Science reported. Researchers believe that elongation of the skull may have been associated with higher social status.

On the other hand, examination of the remains also showed that some of the men had tooth decay, possibly due to their corn-rich diet, and some of the bones were covered with red pigment.

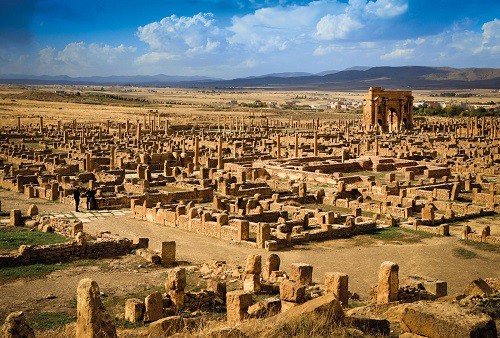

Pyramids at the Moral-Reforma archaeological site near Tabasco, Mexico. Photo: Allthatsinteresting

The remains of these 13 men offer a fascinating look at life and death at Moral-Reforma, once a major Mayan settlement. As Heritage Daily reports, the city began as an important trading post around 300 BC and grew from there. Between 622 and 756 BC, the settlement reached its peak, spanning an impressive 215 acres, where the Maya built palaces, plazas, and pyramids. They eventually abandoned the city around 1000 BC.

However, there is still much that archaeologists do not know about the site, including its original name. Live Science reports that it was allied with other Mayan cities, including Calakmul and Palenque, and that the Maya built as many as 76 structures there. However, many archaeologists believe that the men buried at the base of “Structure 18” may have been sacrificed to appease an underworld god, but it is not yet known which Mayan god the pyramid was built to honor.

As archaeologists continue to explore the site, they hope to uncover more answers. Until then, researchers will have to search for clues in the bones and teeth of men sacrificed at the pyramid hundreds of years ago.

Current science suggests that the elongated skull shape is due to an ancient custom of aboriginal peoples, who squeezed the heads of newborn babies so tightly that they became deformed. But why this phenomenon seems to occur all over the world, in cultures that have no contact with each other, is still unclear.

In fact, these skulls are sometimes almost twice the size of a normal human skull. Many of them are also missing some of the grooves that a normal human has, including the frontal and sagittal grooves. However, they do have an additional groove that runs diagonally across the forehead. The bones of these skulls are often much thicker and more solid than ours.

In Egypt, elongated skulls are not only found, but also decorations and wall carvings depicting elongated heads in significant numbers, many of which date back to the time of the pharaohs. Egyptologists consider these to be depictions of common people’s style of royal headdresses. But unusually long skulls have also been found in mummies, such as that of King Tutankhamun, who was unusually long compared to other people.